‘The Bermuda Triangle of Talent’: 27-year-old Oxford grad turned down McKinsey and Morgan Stanley to find out why Gen Z’s smartest keep selling out

The vice-chancellor stood at the podium in Oxford’s Sheldonian Theatre, her voice echoing against the carved ceiling: Now go out there and change the world. Robes rustled. Cameras clicked. Rows of classmates smiled, clutching degrees that would soon deliver them to McKinsey, Goldman Sachs, and Clifford Chance: the holy trinity of elite exit plans.

Simon van Teutem clapped, too, but for him, the irony was unbearable.

“I knew where everyone was going,” he said in an interview with Fortune. “Everyone did. Which made it worse — we were all pretending not to see it.”

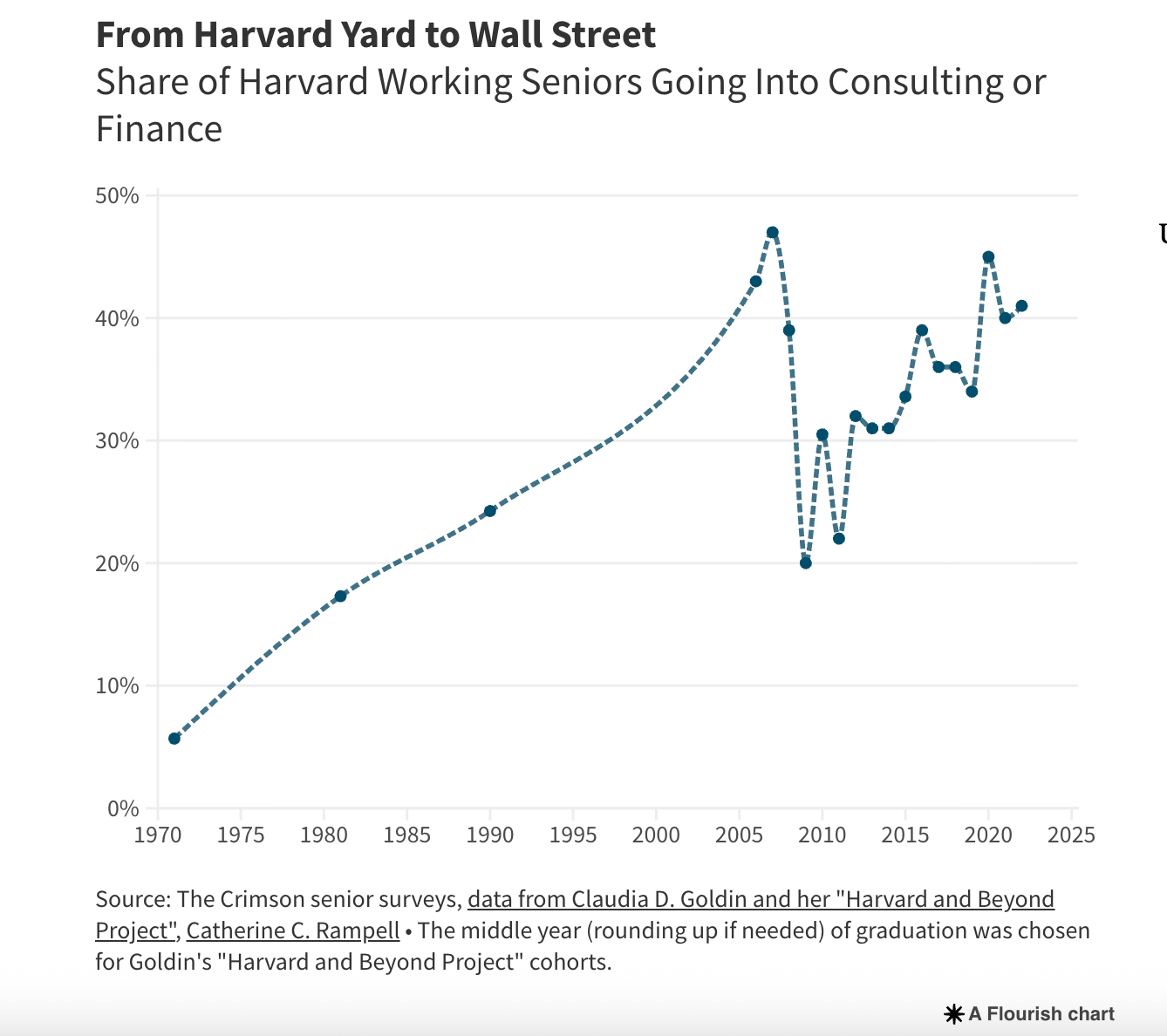

Career paths for the elite have indeed consolidated over the last half-century. In the 1970s, one in twenty Harvard graduates went into careers of the likes of finance or consulting. Twenty years later, that jumped to one in four. Last year, half of Harvard graduates took jobs in finance, consulting or Big Tech. Salaries have similarly soared: data from the senior exit survey for the Class of 2024 shows 40% of employed graduates accepted first-year salaries exceeding US $110,000, and among those entering consulting or investment banking nearly three-quarters crossed that threshold.

Months after that ceremony, van Teutem received two of those kinds of offers: a job at McKinsey or Morgan Stanley. Instead, at 22, he turned both down and spent three years working with Dutch news outlet De Correspondent writing a book about the subtle gravitational pull that makes such decisions feel inevitable.

Van Teutem took on the project after watching the prestige treadmill siphon talented, creative kids into trivial work—and then close the door behind them. Everyone always says they’re just doing their banking job just to get their foot in the door, he noted, but they always end up staying.

“These firms cracked the psychological code of the insecure overachiever,” Van Teutem said, “and then built a self-reinforcing system.”

The Bermuda Triangle of Talent

The book,, The Bermuda Triangle of Talent, grew out of personal frustration. A longtime nerd who was fascinated by economics and politics, he had arrived at Oxford as an undergraduate in 2018 determined, in his words, “to do something good with my talents and privileges.”

Within two years, he was interning at BNP Paribas and then Morgan Stanley, falling asleep at his desk working on mergers and acquisitions with the intensity of “saving babies from a burning house.”

His discomfort wasn’t with the work itself — he isn’t one of the Gen-Zers who thinks all corporations are “evil,” he insisted. “I just thought that the work was fairly trivial or mundane.”

At McKinsey, where he interned next, the work seemed more polished but no less hollow.

“I was surrounded by rocket scientists who could build really cool stuff,” he said, “but they were just building simple Excel models or reverse-engineering toward conclusions we already wanted.”

He declined the full-time offers and instead began interviewing the people who hadn’t. Over three years, he spoke with 212 bankers, consultants, and corporate lawyers—from interns to partners—to understand how so many high-achieving graduates drift into jobs they privately despise. The damage, he concluded, wasn’t villainy, or even greed, but lost potential: “The real harm is in the opportunity cost.”

Money, he found, wasn’t the magnet, at least not at first.

“In the initial pull, most elite graduates don’t decide based on salary,” he said. “It’s the illusion of infinite choice, and the social status.”

At Oxford, that illusion was everywhere. Banks and consultancies dominated career fairs; governments and NGOs appeared as afterthoughts. He remembers his first brush with the system: BNP Paribas hosting a dinner at a fine restaurant in Oxford for “top students.” He applied because he was broke and wanted a free meal—and ended up interning there.

“It’s a game we’re trained to play,” he said. “You’re hardwired that way. You’re always looking for the next level, the Harvard after Harvard, the Oxford after Oxford.”

By the time many graduates realize that there is no gold star at the end – that the next level is simply higher pay and a longer slide deck—it’s already too late. Most people believe they can leave the corporate world after two or three years to follow their dreams, but very few actually do.

“At least I can buy my children a house”

He tells the story of “Hunter McCoy,” a pseudonym for a man who once wanted to work in politics or at a think tank, to illustrate the point. McCoy imagined a future career in advocacy. Fresh out of university, McCoy joined a white-shoe law firm and told himself he’d stay two, maybe three years, just long enough to pay off his student loans. He even had a name for the finish line: his “f–k you number.” That was the sum that would buy him freedom to pursue policy work.

But freedom, it turned out, was a moving target. Living in an expensive city, surrounded by colleagues who billed a hundred hours a week and ordered cabs home at midnight, McCoy was always the poorest man in the room. Each bonus, each new title, pushed his number a little higher.

The trap tightened slowly. First came the mortgage, then the renovations, then the quiet creep of what has been called “lifestyle inflation.” You buy a nice apartment, you want a good kitchen. If you buy the kitchen, you want the knife set that goes with it. Every new comfort demanded another upgrade, another late night at the office to keep it all intact.

“High income stimulates high expenses,” van Teutem said. “And high expenses breed more high expenses.”

By his mid-forties, McCoy was still in the same firm, still telling himself he would leave soon. But the years had calcified into guilt.

“Because I never saw my children, because I was always working so hard, I told myself no, I want to continue for a few more years,” McCoy told van Teutem. “Because then at least I can buy my children a house in return for me missing out on so much.”

The saddest part, he said, was McCoy’s uncertainty about what would remain if he ever walked away.

“He told me he wasn’t sure his wife would stay with him,” van Teutem said quietly. “This was the life she’d signed up for.”

The confession struck him as both raw and deeply tragic, a glimpse of how ambition hardens into captivity.

“It made me happy I didn’t go into it,” he said. “Because you think you can trust yourself with these decisions. But you may not be the same person three years later.”

The long shadow of Reagan, Thatcher, and the Big Three

What van Teutem describes, however, is part of a systemwide phenomenon that’s been decades in the making.

That explosive growth of what researchers call “career funneling,” where students narrow down only two or three industries that are socially deemed prestigious enough to work in, runs in tandem with the financialization and deregulation turn Western economies took in the second half of the 20th century. The neoliberal revolution, driven by former President Ronald Reagan in the United States and Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher in the United Kingdom, expanded capital markets enough to create whole new industries out of manipulating financial instruments; thus, exploding the finance industry. At the same time, governments and corporations began outsourcing expertise to private firms under the banner of market efficiency, giving birth to the modern consulting industry. (The last of today’s “Big Three” consulting firms was founded as recently as 1973.)

As these firms captured an ever greater share of the nation’s profits, they became synonymous with meritocracy itself: exclusive, data-driven, and ostensibly apolitical. They offered graduates not just jobs, but a sense of belonging and identity.

There’s another quieter trap, here, too: the cost of living in the big cities has never been higher. In cities like New York and London—the gravitational centers of global finance—living comfortably has become a luxury good. A 2025 SmartAsset study found a single adult in New York now needs about $136,000 a year to live comfortably. In London, a single person needs around £3,000 to £3,500 a month just to cover basic living, transportation, and housing expenses, and financial advisers now say a £60,000 salary merely buys relative comfort – the ability to save and not live paycheck to paycheck – an amount that only 4% of British graduates expect to make coming out of university.

How many early-career jobs pay more than $136k, or £60k a year? If a 22-year-old comes out of college with the natural desire to explore the big city, a la Friends or Sex in the City, but doesn’t have the cushion of parental support, they have to be within the narrow band of roles that clear the threshold. That means many careers only begin by chasing a salary level rather than pursuing mission-driven work.

Incentivizing risk taking

Van Teutem doesn’t think the solution lies in moral awakening so much as in design.

“You can gear institutions toward change or toward risk-taking,” he said. His favorite example is Y Combinator, the Silicon Valley accelerator that since its founding in 2004 has turned a few dozen nerds with ideas into companies now worth roughly $800 billion—“more than the Belgian economy,” he noted.

YC worked because it reduced the cost of risk: small checks, fast feedback, and a culture that made failure survivable.

“In Europe,” he added, “we do a really bad job at that.”

Governments, he argues, can do the same. In the 1980s, Singapore began competing directly with businesses for top graduates, offering early job offers, and eventually linking senior civil service pay to private-sector salaries. Controversial, sure, but it built a state that could keep its best talent.

The nonprofit world has learned similar lessons. Teach First in the U.K. and Teach for America copied consulting’s recruitment tactics—selective cohorts, “leadership program” branding, fast responsibility—to lure elite students into classrooms instead of boardrooms.

“They use the exact tricks from McKinsey and Morgan Stanley,” van Teutem said, “not as charity, but as a springboard.”

Material pressures still distort those choices. In the U.S., unemployment is soaring for recent college grads as the labor market slackens.

He hopes that universities and employers copy the YC model: lower the downside, raise the prestige of trying.

“We’ve made risk-taking a privilege,” he said. “That’s the real problem.”