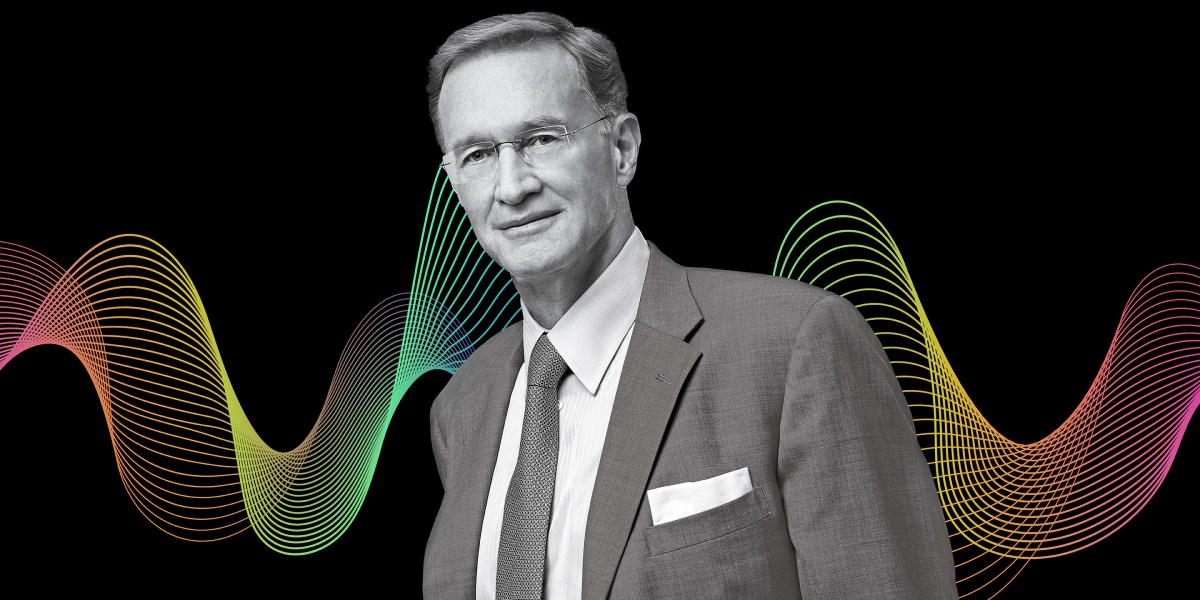

Corning CEO says Jeff Bezos taught him that creating value is less about overcoming failure than, ‘if something is working, double down on it’

On this episode of Fortune’s Leadership Next podcast, cohosts Diane Brady, executive editorial director of the Fortune CEO Initiative and Fortune Live Media, and editorial director Kristin Stoller talk with Wendell Weeks, CEO of Corning. They discuss how Corning became the glass provider for Apple’s iPhone; why Weeks believes it’s a great time for innovation in America; and how Corning has been able to stay in business for almost 175 years.

Listen to the episode or read the transcript below.

Transcript:

Wendell Weeks: Fundamentally, every act of creation is an act of passion. It’s not an act of cold logic. It’s not a framework. It is an act of passion.

Diane Brady: Hi, everyone. Welcome to Leadership Next. The podcast about the people…

Kristin Stoller: …and trends…

Brady: …that are shaping the future of business. I’m Diane Brady.

Stoller: And I’m Kristin Stoller.

Brady: As technology and AI continue to reshape industries, hiring for technical skills remains important. But fostering creativity, curiosity, and empathy are also essential for organizations to remain competitive and resilient. We’re here with Jason Girzadas, the CEO of Deloitte US and the sponsor of this podcast. Jason, always good to see you. Thanks for joining us.

Jason Girzadas: Thank you for having me, Diane.

Brady: So Jason, how can organizations balance the development of human skills and technical skills to drive innovation?

Girzadas: It is a tech-driven world, but still human skills matter. And I think it comes down to being intentional for leading organizations to still invest and have very directed strategies around building human skills. Curiosity, imagination, how-to-team. These are still critical ingredients to creating differentiation and competitive advantage. You know, at Deloitte, we’ve committed to building those skills and have, over time, evolved our programming.

Stoller: Jason could you say, at Deloitte, what role does apprenticeship play in fostering a culture of continuous learning and development?

Girzadas: It’s interesting. There was some time when people thought that apprenticeship and mentorship could maybe be digitized or entirely done remotely. And I think what we’ve learned is that that’s not the case. That apprenticeship and mentorship need to continue to be a formal part of our culture, a part of our learning environment.

Stoller: Absolutely. Well, great insights, Jason. Thank you so much for sharing them with us.

Brady: Hi everybody. Welcome to Leadership Next. I’m Diane Brady…

Stoller: And I’m Kristin Stoller.

Brady: And in this week’s episode, Kristin, we are talking to the CEO of a company that I think is probably one of the most successful companies that a lot of people haven’t heard of.

Stoller: Never heard of. I hadn’t heard of it. It is the CEO of Corning, Wendell Weeks. And Corning, it’s interesting, because their products are so core to America. But you’ve never heard of them.

Brady: Thomas Edison’s light bulb!

Stoller: You’ve got that, you’ve got the Pyrex. You’ve got your grandmother’s cookware, CorningWare. You’ve got the Gorilla Glass, the screen on your iPhone and your Apple Watch. And then, now, you have the next generation fiber optic cables, which are powering the data centers for gen AI and companies like Microsoft.

Brady: And he’s also a leader who’s held in very high esteem. I know you’ve done a feature about him and what this now almost 175-year-old company is doing. But Jeff Bezos, Tim Cook, a lot of the titans of tech look to this man for leadership, for what the next generation is going to look like.

Stoller: And consider him a close friend. I mean, this is the first and only time I’ve ever gotten a call from Jeff Bezos, who was glowing about Wendell. Andy Jassy, Ford’s Jim Farley, everyone really respects him. And he’s on Amazon’s board. They look to him for advice, too.

Brady: And look, this is a podcast about leadership. This is a man who is the child of two alcoholics. He’s made very conscious choices for how he wants to lead, his mindset around followership. So I think there’s a lot to learn, not just about what’s around the corner, but what’s within the great leaders we have in our time today, and I really enjoyed it. I hope you will, too.

Stoller: Alright. So Wendell, it has been almost a little over a year, I believe, since I last went to visit you in Corning. So, thank you so much for joining us.

Weeks: This time in your home.

Stoller: Exactly.

Brady: Welcome to our home.

Stoller: So, I was talking to Diane about our time in Corning, and I think one of the things that I loved most about it was all the amazing stories you told. Not just of Corning, but of all these partnerships and other CEOs you talk to. Diane actually had a great point yesterday where she said, It’s amazing that CEOs called me to drop your name instead of the other way around. I’ve never had Jeff Bezos call me before. That was thanks to you. So I guess the place I want to start is—talk to us about these partnerships you have and these relationships you have with CEOs. Do you have a best story of working with one in a professional context, and personally, that you think demonstrates the value you bring as a CEO and leadership?

Brady: That’s a lot of pressure.

Weeks: It’s been such an important part of my life, all the different folks who’ve helped make Corning be great and help me be better. So it’s hard to pick out one that’s great, you’ve talked to a number of them. I’ll go back to one that’s fun.

Stoller: Okay, we like fun here.

Weeks: So, a fun one to tell would be about Steve Jobs. Steve, when he first wanted to do the iPhone and wanted us to invent a more durable, transparent material, he and I met through very funny circumstances. You know that story, but then subsequently…

Brady: Wait, I don’t know that story. You met through funny circumstances?

Weeks: So, a mutual friend had introduced us electronically, because I wanted to show him an innovation that I’d been working on. And what we’d done is we’d come up with a way to make a synthetic green laser, which I won’t bore you with how cool that is and why it’s cool, but it’s cool. And our idea was that phones had all the processing power, but the displays were really small, and with semiconductor lasers we could turn each phone into a projector. And so that was our idea. And so I shared that data with him, and he came back and said, that’s a really impressive technical result, but, that’s the dumbest idea I’ve ever effing heard in my life. And I was like, the dumbest idea? I feel proud. That’s hard.

Stoller: That’s quite an honor from Steve Jobs.

Weeks: But the good news is, you’re working on the right problem, which is [that] we need a larger display. So he then just picked up the phone to call me, and he got put into Corning’s general number, and the operator answered. And he goes, I’m Steve Jobs, put me through to Weeks. And the operator says, We would be glad to put you through to Mr. Weeks’s office and let you talk to his executive assistant, and he goes, I am Steve…

Brady: …effing jobs, yeah…

Weeks: …put me through to Wendell. And the Corning operator says, Hello, Mr. Jobs, I’ll be happy to put you through to the executive assistant…so he hangs up and sends this email to our mutual friend Andy. So I tried to call Wendell, typical East Coast bullshit. They would only put me through to his executive assistant. I picked up the phone, and I called Apple’s general number and said, Please put me through to Steve Jobs. They say, if you would fax us a fax, fax us the reason for your call. And then if it goes through that screen, then we’ll allow you to talk to his executive assistant. Back to the email. You know, just tried to call Steve, typical West Coast bullshit. Like, who uses a fax machine versus… [I’m] copying Steve on the whole thing. Steve, you want to talk to me? This is my mobile number, and that’s ultimately—and he called me out of a board meeting, actually—took the call.

Stoller: Good thing you took the call, too.

Weeks: And that’s how we ended up working together on the iPhone.

Stoller: Yeah, well, people don’t associate Corning with the Gorilla Glass in the iPhone. I think that was one of the things I was surprised to learn.

Weeks: You were surprised to learn that it was Corning?

Stoller: Yes, because I associate Corning with Pyrex, with all the old…

Brady: Well, I always think, I do associate you with innovation. I always think, you know, this is what, four millennia we’ve been making glass. I used to go to the Corning…I told you I used to go to the Corning Museum en route to other destinations. But I do think you’ve been on the forefront of innovation, and what have you done with glass that many others—you know, hundreds, thousands of companies, it’s one of those things that could have been commoditized and sent to China—what have you done at Corning that’s really sort of put you on the cutting edge, to the point where you’re seeing as much as a tech company as a commodity company?

Weeks: I think it starts with being deeply passionate about our little slice of the periodic table and our little slice of the electromagnetic spectrum. We try to be the world’s best at that, and we attract other folks who believe in the same highly passionate way. The wondrous thing this material is, which is it sort of has the structure of a liquid, yet it is a solid at room temperature. And all of the magical things that we can do with that is the core of so many of our innovations. Whether it is the first low-loss optical fiber, whether it is Gorilla Glass, whether it is materials that can go from a rocket ship, all that friction, all that heat in the deep space, and be fine. All of these wonderful things that we think we can do with this material to try to make the world just a little bit better with our limited in scope, but deep knowledge. And so we start there, and then we add to that investment, and then we add to that just fabulous relationships with real innovators to try to understand what we can do to make their stuff better.

Stoller: One of the things that I think is so interesting about Corning is that you have such a decades-long research and development process. R&D is so important to you, you were telling me. And even now, with these new fiber optic cables for gen AI, those were years, decades in the making, correct? So how do you, in a world where there’s such short-term investor pressure, how do you justify investments that may not pay off for decades later and may not pay off at all?

Brady: One-hundred-fifty-year plan?

Weeks: So yes, you’re right. We have one of the very oldest research labs in the U.S., over 100 years old. And so many other research labs have faded or gone away, and I think it’s because we don’t—you know, the categorization is, everybody says that it’s a research lab. It’s an R&D lab. But actually, we’re just builders. We don’t just research to research. What we’re always trying to do is build something that is going to solve a problem, that is going to make things better. And because of that, there are very few divisions between, for instance, my job and a bench scientist. I mean, I spend as much time with our bench scientist as I would with our customers, as I would with my CFO, as I would… and it is that, which is always seeking to build, that I think has been our secret to why it always works out for us in more traditional research labs. Which look a little more like academia, you know, have a harder time sort of being relevant in a capitalist world.

Stoller: What would you say was the best bet that you think the company’s made in its almost 175-year history?

Brady: Or your history, the ones you’re responsible for?

Weeks: The best one was the lightbulb for Edison, hard to compete with. That was a really good idea. Light is a good idea. So that was, that’s one. But you know, there’s been so many. Cathode ray tubes for Sarnoff and RCA to make televisions. The first liquid crystal display substrate that makes all of the flat panel displays that you’re used to seeing, the first low loss optical fiber, the ceramic substrates that clean the air of your emissions from your vehicles, the pharmaceutical packaging that made your COVID shot possible. It just keeps going on and on and on. Sometimes it’s small things, and sometimes it’s big things. The Gorilla Glass in the iPhone, is like a huge thing. The Gorilla Glass to make that work, well, it definitely helped. It’s a key thing. And sometimes it’s smaller still. How do you make a surface that doesn’t reflect so that it makes it easier to read outside? There’s all these different things we try to constantly do. How do we make your display use less power? All these sorts of things, and that is the core of what we do. Our why is to do life-changing innovation and help others be successful with it.

Brady: You know, as we were sitting down, you talked about “followership,” and I want to get to that, but I’d love to get a sense of what shaped you as a leader. And one of the things that impressed me when I was reading about your background is just the fact that you actually talk about having two parents that were alcoholics. You know, that’s something that’s run in my family, and I think about how it shaped me. How did that shape you when you think about just growing up and what it’s done to your mindset as a leader?

Weeks: Well, if you have it in your background, you realize that you come from a pretty chaotic background. So if you come from chaos, you can go a couple of ways. Right? I was lucky that I was always smart enough to realize that if I wanted to be a better man, I needed to hang out with better people, because I’m pretty malleable. And as a result, that’s why I joined Corning. It was when I first met the people from Corning, they were all just such great people. People that led lives. Sometimes they’re small, sometimes they’re larger, but their lives are stable. They served their communities. They served their families. They had work they really liked. And Viktor Frankl writes, in Man’s Search for Meaning, that what you should treat a man like, is what he could be. If you treat a man as he is…

Brady: …nothing aspirational about that…

Weeks: Right, if you treat a man as he is, he’ll never improve. If you treat a man as he could be, then he can accomplish great things, and Corning created that for me. So one of the big reasons I joined Corning was because of my background, coming from relatively chaotic roots, and boy, it’s worked for me.

Stoller: I’m curious, because you’ve been at Corning for most of your career. I know you were at, was it PwC before?

Weeks: Briefly, yeah.

Stoller: How do you sustain yourself as a leader? Has there ever been any times you’ve wanted to quit, and then I’ll ask my second part of the question, but what keeps you going?

Weeks: I wouldn’t say there’s ever a time that I wanted to quit. Whenever I’ve said that I hate my job, it isn’t that I hated my job, I hated the way I did my job that day. These jobs are great jobs, right? They’re just hard to do, and if you don’t do them well, you don’t think highly of yourself or the job you did. So it’s that, and I never really wanted to quit. I’ve had plenty of challenging times. I’ve had times when I’ve wondered if I’m the right person, but these jobs are just—they’re terrific jobs. I mean, I love going to work, and I always have.

Stoller: When you say, if you’re the right person, are you talking about the dotcom crash or another time?

Weeks: For sure that was one, right? But there’s been others. Our mission, back when I first became president, post-dotcom crash, I redid our whole strategic framework and said, our mission is another 150 years of innovation and independence. And all of the things that you have to do to do that, we studied deeply. All sorts of different companies’ histories, as well as ours. We realized how rare that is and how different you have to be to do that. Like, a great statistic on this would be, take a look at the original S&P 500 list, which was like ’57, ’58, right? So of that original 500, you know, there’s 10% of us left, 50 to 53? Something like that left. That is just since 1957, which to you seems like a long time. To me, that’s my lifetime, right? And think of everything it takes to be one of the 500 most valuable companies on U.S. exchanges, the most important exchanges in the world. How good you had to be to be one of all of the hundreds, thousands of companies to get there? And then you get there and you can’t survive as long as a normal human lifetime. We just took another look at the data, from 23 years ago when I put this new framework in place, and going forward, half of the S&P 500 is gone.

Brady: Well, the speed of disruption is clearly speeding up. I think about Jim Collins, you know, Mr. Good to Great. But also, Why the Mighty Fall. And one of the theories is doing the right thing for too long. What do you think of as the key for staying ahead? Because a 150-year plan is tough when you’re in an AI environment where it’s hard for any of us to predict even what comes out of this. What are some of the principles that you think are going to let Corning sustain?

Weeks: I think people take business and innovation and they try to make it fit in business school books or in frameworks or what-to-do books. And they forget that, fundamentally, every act of creation is an act of passion. It’s not an act of cold logic. It’s not a framework. It is an act of passion. And for passion to activate, you really need two things, right? You need to actually be good enough at a thing that you understand it deeply enough that you could be passionate about it. It’s hard to be passionate about a thing that you don’t understand deeply, that you haven’t dedicated your life to, that you haven’t dedicated time to. So we’ve dedicated our time, our efforts, generations of people, sometimes multiple generations in a family as part of Corning, with deep passion about what we’re good at, our three core technologies, that’s what we’re passionate about. And then, the other piece of passion is, you need someone to practice it with, right? And that is all about being trustworthy, having deep trust-based relationships with people that are smarter than you on what they’re doing. And so our success through that time is really with those two things. How do we behave in a way that our communities can trust us? Our people totally trust us. Our customers trust us. The individuals there have such relationships—they share with us, like, here’s what our problems are, here’s what we’re thinking about, here’s where we’re struggling, here’s what I’m confidentially dreaming of doing, and then offer us to be talented enough at our little, tiny thing to help them make their big thing work.

Stoller: What do you think? And I’ve asked you this before, but I’m curious again, to ask it to you a year later, because you’ve been betting so big on this gen AI, this next wave that’s coming. What do you think is next, after this, that you’re really excited about?

Weeks: Well, first of all, gen AI is really the beginning, if you think about it, from our side. So we start with photons. Photons for us is what it’s about. I know other people think it’s about GPUs, right? I know that. For me, it’s about photons. And so that is still at the very beginning, the next frontier for us in AI, is what’s called the scale-up piece of the network as fiber replaces copper, fiber optics photons replace electrons, deeper and deeper in those GPU neural networks. And so we’re in the midst of doing a bunch of inventions there, working with great companies to [see] how we bring some of our ideas together with theirs to make AI as great as it can be from a networking standpoint. But also, while we’re doing that, we’re firing up what will be America’s largest solar plant for ingots and wafers. And little-known…probably 98% of polysilicon solar, which is the most significant technology in solar, is sourced in China. The fundamental material, the ingots and the wafers, probably 45% of that is in Xinjiang province.

Brady: Lucky you on the tariff front, then.

Weeks: Yes, so what we believed is, we could bring our skills—because we use that same material to make semiconductors—that we could take that skill and apply it to solar. Because what we believe deeply is that the U.S. needed its own independent source of all sources of energy, and that that has been a journey, and we’re just in the midst of starting up that plant. So while AI is going on, we’re investing in solar. You mentioned recently the big announcement we have with Apple. So while we’re doing AI, we’re also investing in the next generation of mobile consumer electronics. We’re also trying to bring new innovations to automotive. The key when your mission isn’t to optimize the share price in any given time period, and instead it’s for another 150 years, is in the upswing of the business that’s really working well today. What you don’t do is, you don’t pour all of your investment into that. You create the seeds in other areas in a balanced way, because all things go through cycles. And what we want to do is make sure that as our big businesses go through cycles, that we have the next innovation for the next generation of people that will follow me to carry on this tradition.

Brady: So, Wendell, talk about being—you’re on the Amazon board. And you know, some CEOs think it’s incredibly valuable to be on a board. Others are like, I’m too busy. Why that board? And just generally, what have you gotten out of being on a board as a CEO?

Weeks: If you get an opportunity to learn from folks like Jeff Bezos or Andy Jassy, say yes.

Brady: So what have you learned? Tell me what you’ve learned.

Weeks: So, many things. I’ll take one from Jeff Bezos. This is so important, this is a very true thing of most great entrepreneurs, is they view risk differently than you and I. I have a great Steve story about that, too. Which is, they have a much more even view of risk. Most of us view risk as all of the ways that you personally can look like an idiot, right? And it shades the way you look at things. Jeff looks at things very straightforwardly and is damned fearless, right? And then what he believes, and he’s taught it to me, and it’s true, is that all the value you create isn’t in lamenting how you failed here, or failing fast, or any of this other stuff everybody talks about. It’s doubling down on what works. If something is working, double down on it. And if that works, double down again. Because it is so valuable for something that works, because that’s an annuity. A failure is just a capped amount of money. That is what it is. It creates no great value. So, double down on what works. Relentless customer focus, both him and Andy. It is next level. That is not just a saying. At Amazon, they are focused on you as a customer, making your customer experience better. So many things I’ve learned from these guys.

Stoller: Well, now I’ve got to know the Steve Jobs risk story, because that sounds really tempting, too.

Weeks: So the Steve Jobs story is, my board of directors sent me back to tell Steve, Yes, we can do it, because we invented it, but I can’t do everything. So, you should get a second source, because I don’t know that I can make it at the scale that you need. And so Steve and I are sitting alone, and he says, No, you’re going to do all of it. And I’m going, What I’m telling you is, I really can’t. I know. He goes, No, you can do it. I go, Hmm, pretty sure that I know more about this than you. I took a hand in inventing this product, and I actually know how they made it. I know this better than you. And he goes, No you don’t, you can do it. And I go, Really, I can’t. And he goes, Do you know what your problem is? And I go, Well, you know, I don’t know, I’ve got a lot I’m sure, what do you think my biggest problem is? He goes, You’re afraid. What an amazing thing to say. He says, You’re just afraid. It was, like, a shocking thing, and I go, I don’t know that I’m afraid. He goes, Yeah, no, you’re afraid. You know what you’re afraid of? You’re afraid I’m going to launch the biggest product in history, and I’m not going to be able to do it because you failed, and I’m going to eviscerate you.

Brady: A fair concern, I’d say.

Weeks: That’s what he said. Now the truth is, I will. That’s true. If you fail, I will. But look what you’re doing. You’re worried about you looking bad, and you’re keeping your people from greatness. Imagine how they’re going to feel, the folks that are working in that plant in Harrodsburg, Ky., if they’re part of this. So you’re putting yourself above them and your company. And I said to him, You’re right, I’m afraid, and I’ll go fix that. And we went away, and we said yes, and that is a good Steve Jobs story.

Stoller: And now, full-circle moment, because Tim Cook made this announcement about a $2.5 billion commitment to produce all of the cover glass for the iPhone and Apple Watch at your Corning Kentucky facility. Tell us about that. And was getting the call from Tim like getting the call from Steve? Or was it a little easier?

Weeks: Tim’s a lot nicer. So yeah, I think that is just just such a terrific story, and it’s so spectacular for our people in Kentucky. That’s a plant that’s about 70 years old. We started it in the Cold War, so products that were valuable during the Cold War. And the way Corning thinks is, if we make a commitment to a community and to people, it’s our job to come up with new products, new things that those folks can do. And it isn’t right for a factory to die and a community to die because of our lack of imagination when the product naturally went through maturation and exited. So when we did photochromics, we invented that, we brought photochromics there, and we made sunglass lenses there, because we knew optics from doing all sorts of telescope optics. And then we had this idea to do liquid crystal display glass. And so we did that there. And then that is the first place we did Gorilla. And so what this enables us to do is, we’re going to triple the capacity of this. We’re going to do a joint innovation center. We’re going to put in like three new generations of technology. So this will be the world’s leading production site for any of these types of materials. And it’ll do 100% of Apple’s iPhone and Apple Watch products, and we’ll do it in a co-innovation manner with one of the greatest innovative companies in the world in Apple.

Brady: You know, as you’re talking, Wendell, I’m thinking about the ways in which you defy conventional wisdom. You’re not in Silicon Valley only, you’re talking about tripling at a time when a lot of leaders talk about a talent shortage. What’s the environment like? Give us a sense—you sound very optimistic about the growth prospects. What’s it like to be an innovator in America today? Because I get mixed signals from different leaders. How are you finding it?

Weeks: I think it’s great.

Brady: All right, specifics.

Stoller: Explain.

Weeks: I’ve been through a lot of innovation cycles. At this point in time, the level of innovation that is happening here in America, and around the world, but also centered up here in America, is stunning. AI, the folks that have brought you AI, right? That is American-born innovation, and they’re driving that whole edge. Now, it takes a global village to do something like AI. That’s a whole different debate, but there’s just so much innovation going on in so many areas. When you have a transformative technology like this, then all of a sudden people start innovating in power, right? They innovate in photons. Of course, I have to throw that in there, right? And area after area—we’re learning new construction techniques. And this is a great time to be an innovator in the U.S., and we never have a problem getting talent.

Brady: So, you’ve told us about the leadership advice that was given to you. Let’s have you give some advice to people who want to be in your seat, to the next generation of leaders. What would you say?

Weeks: I’d say that the piece of being a leader that is most misunderstood, in my opinion, is being a follower. Any given day, I am following people that supposedly work for me. The way we work is, what are you a subject matter expert on? Who’s the right person to lead this team at this moment on this topic? And that’s what matters to us. That doesn’t mean that if you’re the expert, we don’t question the heck out of you. Just expertise of self isn’t enough, because it’s something that’s really innovative. No one really knows exactly how it’s going to work, but an expert knows how to think about that particular problem. And so I think leaders over-express, because we consume too much business junk food literature, but fundamentally, leading is an act of service, and it’s in service of various things and various constituencies. And whenever you flip that and you instead are the one that is being served, at that moment you have lost the plot. And the way you learn that is through the bulk of your life as a server, which is what followership is about. I am going to trust you, with my family, with my community, with my career, to help us make better… that’s a big thing. That’s a social contract. And so, first, be a great follower, and then you can learn how to be a great leader.

Brady: I love that.

Stoller: Wendell, thank you so much for your stories, for your philosophy. Thanks for joining us.

Weeks: My pleasure. Thank you for having me.

Brady: Leadership Next is produced and edited by Hélène Estèves.

Stoller: Our executive producer is Lydia Randall.

Brady: Our head of video is Adam Banicki.

Stoller: Our theme is by Jason Snell.

Leadership Next episodes are produced by Fortune‘s editorial team. The views and opinions expressed by podcasters and guests are solely their own and do not reflect the opinions of Deloitte or its personnel. Nor does Deloitte advocate or endorse any individuals or entities featured on the episodes.